Somewhere Between the Strokes

One of the things I like most in life is wandering through museums and galleries. Visiting them feels like stepping into a space surrounded by the work of other people’s minds – materialised into paintings, objects, artefacts, and all kinds of art forms. It’s comforting, somehow. Like falling into someone else’s thoughts for a while.

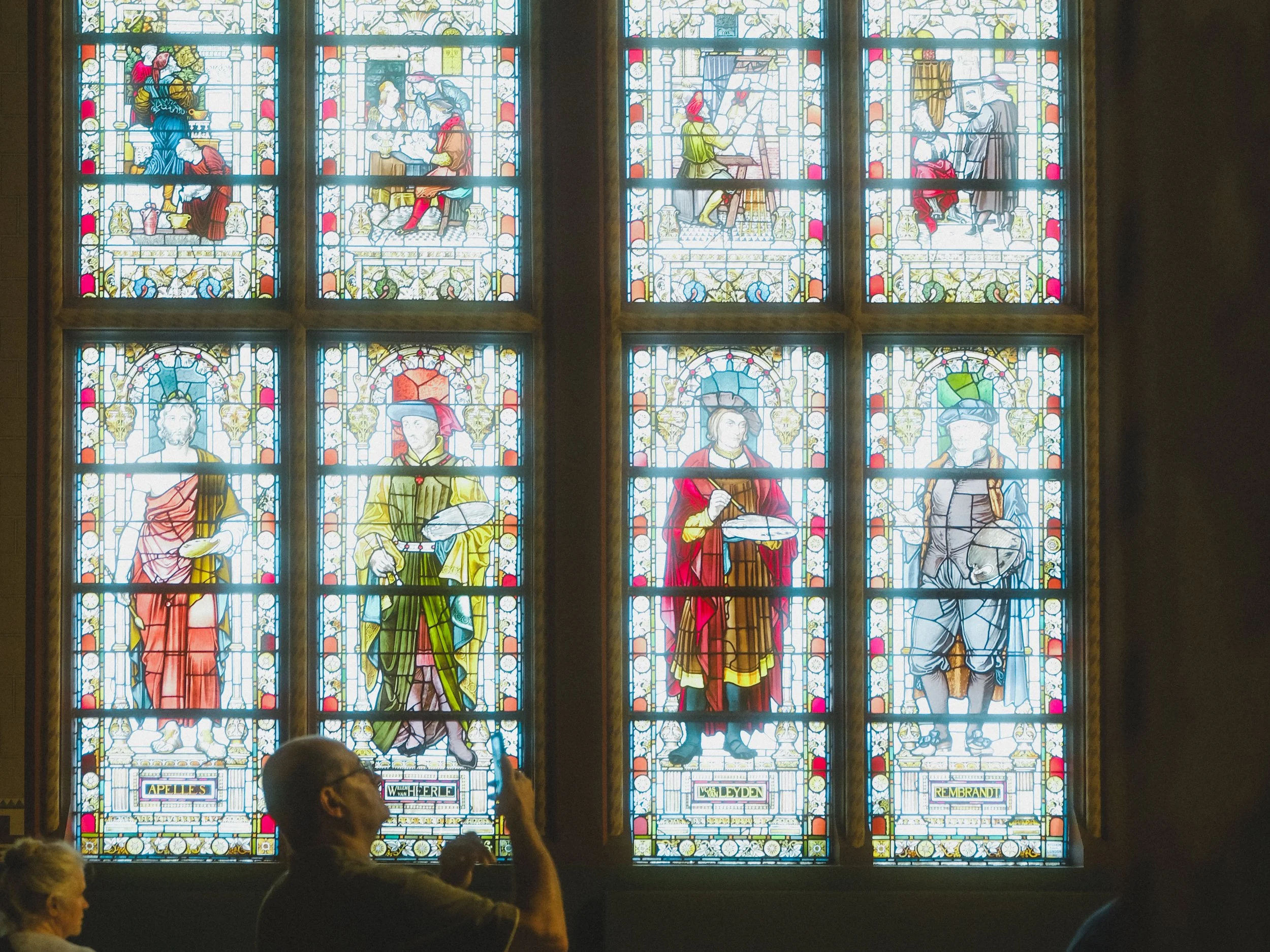

Whenever I travel, I try to visit at least one museum or gallery. It doesn’t matter if it’s big or small, famous or forgotten. I just want to know how people from that place saw the world – or how they wanted others to see it. In Amsterdam, I found myself at the Rijksmuseum. I hadn’t planned to stay long, but time slipped in that strange way it sometimes does. Hours passed. Maybe even a whole day.

Since my days as an art student, I’ve always had a soft spot for the Dutch painters of the Baroque period – Rembrandt, Vermeer, Frans Hals. I call them the Masters of Light. There’s something about their way with illumination – how they understood the way light moves, how it touches things, how it lingers in corners. Their work holds a kind of theatricality, a quiet insistence on finding beauty even in shadow. These paintings feel less like pictures and more like small, self-contained worlds – ones you can step into, or get lost in for hours while tracing the details.

I love realistic painting. Somehow, I always feel it never tells the whole story, even though that’s what it appears to promise. It carries a kind of mystery with it. What you see is never just what’s there – it’s what the artist saw, what they felt, what they chose to leave behind. And somewhere between the brush strokes and the empty space, something begins to slip out of reach. You’re not quite sure if the moment really happened, or if it’s a memory reshaped by imagination. That uncertainty is what draws me in. The image never settles. It keeps shifting, just beneath the surface.

When I was younger, I only saw these works in books. Small, flat reproductions with neat little captions. I never really understood the fuss. But then I saw one in real life – stood in front of it, close enough to see the strokes, the cracks in the paint, the way the light hit the canvas just so, and something shifted. It was like meeting a person you’d only ever seen in photographs, then realising they were taller than you expected – or at times, smaller than you’d imagined. The illusion of scale breaks. One never truly understands a painting’s scale until it is encountered in physical space.

Perhaps the greatest difference in viewing a painting in real life is this: the way it restores dimensionality to visual imagery. Painting, as a medium, is never flat. On screen, you can pinch and zoom all you want, but you’re still seeing a surface without substance. You miss the sensation of tactility. You don’t feel the weight of the pigment, or how the paint lifts – just barely – off the canvas. You don’t notice how time has settled into the varnish like dust into old floors. In a world obsessed with sharpness and clarity, paintings offer something else. A kind of softness. They ask you to stay longer. To look deeper.

In the museum, the air is still. People speak in half-whispers. Footsteps echo softly across the wooden panel floors. Time becomes elastic. The past, the present, and whatever exists in between begin to blur. And maybe that’s why I keep returning to places like this, not for answers, but for atmosphere. For the space to drift. To stand in front of a painting and feel, if only for a moment, that the distance between me and someone from another century has collapsed.

Text and images by ANATOMY OF THINGS